Coffs Harbour

Coffs Harbour

The Holocene Epoch (which we are currently in) started around 11,700 years ago at the end of the latest glaciation. Humans were at the time in their Neolithic Period, the last of three periods in the Stone Age. The Neolithic period saw a quantum shift in civilizations around the inhabited world. The shift may have been due to the rising sea levels. During the Pleistocene Epoch, or the latest glaciation, sea levels were quite a bit lower than they are today. It would have been possible to walk most of the way from Africa to Papua New Guinea, and then onwards to Australia. With readily available new territory it was easy enough to simply move on when the resources of any one area were exhausted, and so hunting and gathering made sense. But as the various land bridges flooded over, pockets of civilization became more static, the bulk of the population staying in one place and only the explorers and colonizers moving about. So neolithic man experimented with a new idea - agriculture.

Managing the forest, encouraging certain things to grow and discouraging others, made for a more stable food supply. But once you started to modify the forest into a farm, it was not easy to move. The evidence will now be under hundreds of feet of water, but it is easy to imagine a succession of early attempts at farming by the neolithic people, who very likely lived near the sea. In fits and starts, over the course of nine thousand years, the sea level rose by 130 meters. It continues to rise today at a rate of about 1.8 mm per year. During three meltwater pulses, the sea level would have risen dramatically in one person's lifetime. So it would have been reasonable for them to move inland and to higher ground to build their immovable farms.

In the highlands of Papua New Guinea, in the Wahgi Valley, there is a wetland called the Kuk Swamp. It is an alluvial fan that has silted in the basin of an ancient lake, filling it with rich material. Around 9,000 years ago someone started building drainage ditches in the swamp and was apparently growing Taro, a root vegetable something like a potato. By 6,400 years ago, based on the phytoliths (cellular fossils) found in the soil, they were also growing Sugar Cane and Eumusa, likely the first cultivated fruit.

Over the years, more crops were added, technology advanced, and by 1500 B.C. the Austronesian people of south-east Asia were trading and colonizing as far away as Madagascar, East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. The items they had to trade included coconuts, sandalwood, cinnamon, cassia, sugarcane, and the new fruit, Eumusa. Eumusa was edible, possibly tasty, but had enormous inedible seeds. Nonetheless it was such a novelty that it quickly spread throughout the known world, in India by at least 600 B.C. and China by 200 A.D.

In 650 A.D. efforts in Africa succeeded in cross breeding two strains of Eumusa - Musa Acuminata, which has an unpleasant taste, and Musa Baalbisiana, which is too seedy to really eat. The result was smaller, tastier, and more importantly, seedless. The new hybrids were about as long as one's finger, and so they aquired the name Banan, Arabic for Finger.

The new Banana hybrids were, of course, sterile. Hence the lack of seeds. So to make more of them, you have to take cuttings (pups) and clone them. Even identical clones have some variation, however, and good variations were of course favoured. So over the years, Bananas became longer and sweeter. And as they improved, they started travelling back towards their place of origin, along the Maritime Silk Road, towards the South Pacific. The first stop on this road was the island of Mauritius, eleven hundred miles the other side of Madagascar from Africa.

In 1834, Mauritius was under British control. It was and still is a highly diverse nation, the only nation in Africa that has Hinduism as its primary faith. So the island was rife with missionaries. And also plantations of various things, including bananas. As missionaries went home they took souvenirs, which were sometimes exotic plants. And so the Chaplain of Alton Towers (the seat of the Earls of Shrewsbury) found himself in the possession of some banana trees which he did not want. He gave them to William Cavendish, the Sixth Duke of Devonshire. William handed them over to his gardener, Joseph Paxton. And there the story should have ended, with some dead plants that cannot grow in England.

But Joseph was more than your average gardener. He had been experimenting with a design for a house made largely from glass for the previous two years. This ingenious new concept allowed the growing of such exotic things as pineapples, right in Devonshire. So when he received the banana specimens he got right to work on them, selecting and perfecting over the generations until he had come up with the Cavendish Banana.

And now we have to leave the Cavendish banana for a bit and talk about another. As the banana spread east from Mauritius people naturally continued selecting the best specimens to be cloned into future generations. By the time Nicolas Baudin carried some banana corms from Southeast Asia to Martinique in the Caribbean, they had morphed into a new variety: the Gros Michel, the Big Mike. The Gros Michel was larger and sweeter than the Cavendish, and huge plantations in Jamaica, Honduras, Costa Rica and various countries in South America all grew this one cultivar.

Meanwhile, the Cavendish, being a British thing, was showing up in the colonies. Especially Australia. There were plantations in Cooktown, Cairns and Innisfail. But the first truly commercial operation was started in Coffs Harbour in 1891 by a German immigrant, Herman Reich. Import duties ensured that the variety of choice remained the British Cavendish.

And this should be the end of the story. There were two main cultivars of banana in the world: the Gros Michel primarily in the Americas, and the Cavendish, in the colonies. All of them monocrops; identical clones of every other member of their variety. And that brings us to Panama Disease.

Fusarium Oxysporum Cubense Tropical Race 1 fungus, or Fusarium Wilt, causes the banana plant to block its own water channels, preventing water and nutrients from travelling to the leaves. So the plant turns black and dies. The fungus can live for decades in the soil, so once a plantation of bananas has become infected, you will never grow that variety of banana there again. But the thing is, Fusarium TR1 only affects Gros Michel, not Cavendish. So you get songs like Yes, we have no bananas in the States but not so much in Australia. By the time Carmen Miranda was telling us that bananas have to ripen in a certain way her entire industry was about to suffer a huge setback. The 1950s saw the end of commercial production of the Gros Michel worldwide. Nowadays there are hundreds and hundreds of different banana varieties, sweet ones coming mostly from the Musa Acuminata line, and plantains having more Musa Balbisiana in them. But most people grow Cavendish, which are not susceptible to Fusarium TR1. Apart from the "specialty" bananas such as Lady Finger and Ducasse, every commercially produced banana on Earth is an identical copy of every other, making the humble banana the largest organism there ever was.

And this should be the end of the story, with the entire planet enjoying a monocrop with no genetic diversity whatsoever and completely impervious to Panama Disease. Version one. But Panama Disease is now at version four, and Cavendish bananas are susceptible to that. Biosecurity is a rigorous endeavour for anyone who runs a banana plantation. But it is inevitable: bananas are doomed.

So let's go to Coffs Harbour and visit the Big Banana Fun Park while we still can!

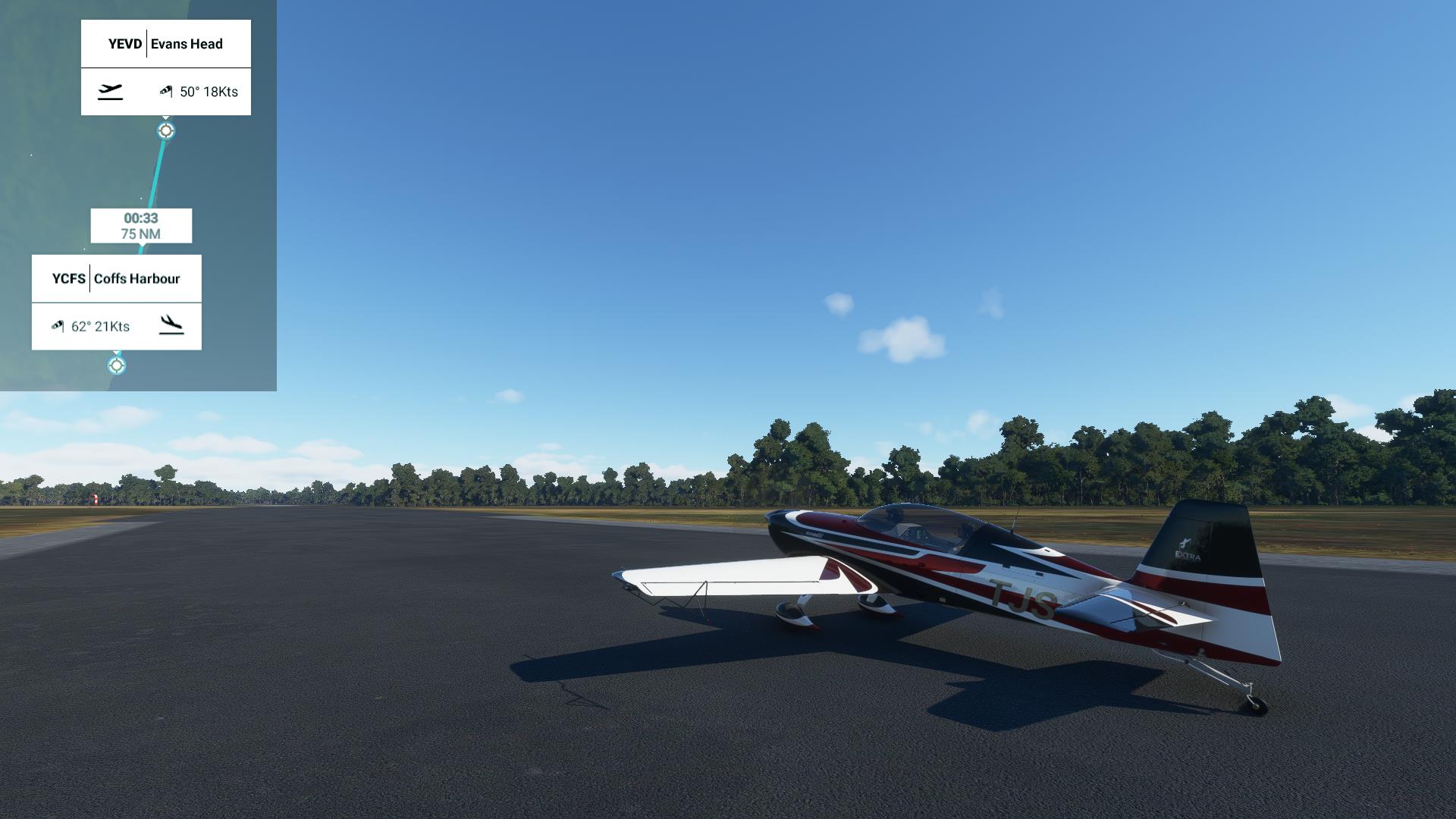

So long Evans Head.

So long Evans Head.

|

Well that's interesting. No idea what it is though. Maybe a new subdivision.

Well that's interesting. No idea what it is though. Maybe a new subdivision.

|

Yamba. Big on tourists.

Yamba. Big on tourists.

|

We'll shave a corner off by going overland.

We'll shave a corner off by going overland.

|

Somewhere down there its all bananas. I really don't know what they look like from the air.

Somewhere down there its all bananas. I really don't know what they look like from the air.

|

And here we are in Coffs Harbour. A double victim of the flooding. While the town itself was inundated, the banana plantations are being hit hard with Panama Race 1, which spreads dramatically with heavy rain. One grower will have to switch from Lady Finger to Cavendish because his soil is infected now. That will cost him a year.

|

|

Time to go bananas.

Time to go bananas.

|